Photographer Robert Bergman: Outsider looking in

Bergman's street portraits of unidentified Americans have been compared to the Old Masters. Yet recognition has been a long time coming

Street life ... Untitled, 1990. Photograph: Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London/Robert Bergman

As photographers go, Robert Bergman is, if you'll pardon the pun, a late developer. He took his first photograph in 1950, when he was six years old. Last year, aged 65, he finally had his first show at the prestigious National Gallery of Art in Washington. Previewing the show, the Wall Street Journal described him as "a cult figure" whose work had long been "isolated from contemporary tastes".

In the last few years, though, Bergman has belatedly become a hot property. A few weeks after the Washington show opened, he was feted by a retrospective at P.S1 in Queens, New York. Now, finally, theMichael Hoppen Gallery in London is hosting the first-ever European exhibition of his work. It is, to say the least, an intriguing show.

Since the mid-80s, Bergman has been photographing on the streets of Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and New York. He is not a street photographer, though, prowling the pavement for that elusive moment where it all comes together. Instead, he is a street portraitist who always asks permission of his subjects, and moves around them slowly and patiently, shooting in colour using a 35mm Nikon. His portraits possess a heightened intensity and painterly quality that is rare in work made outside of the photographic studio. Indeed, in a press release, the Michael Hoppen Gallery compares them to "the most luminous of Renaissance and old master paintings" as well as Goya and Van Gogh.

Bergman's work seems to inspire this kind of hyperbole. When his first book, A Kind of Rapture, was published in 1998, Toni Morrison wrote: "Occasionally there arises an event or a moment that one knows immediately will forever mark a place in the history of artistic endeavour. Robert Bergman's portraits represent such a moment, such an event."

'Strange, sad power' ... Bergman's portrait of a woman. Photograph: Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London/Robert Bergman

'Strange, sad power' ... Bergman's portrait of a woman. Photograph: Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London/Robert Bergman

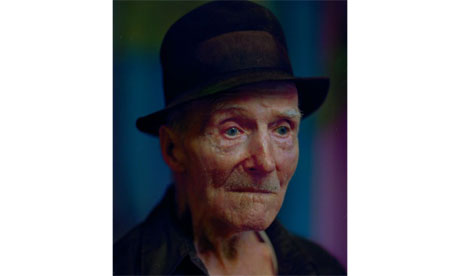

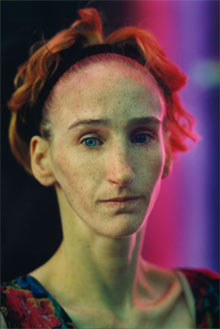

Bergman's subjects often seem to be street people or outsiders, and many gaze away from the camera or stare fiercely into it. One old man with a hat possesses a face that is sad, bemused and world-weary, but also appears somehow theatrical – as if he has just walked out of a production of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. A red-headed woman with piercing pale blue eyes seems almost otherworldy in her gauntness, the luminous vertical strips of pink and violet light in the background adding to the strange, sad power of the portrait.

Sarah Greenough, senior curator of photography at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, noted Bergman's "ability to put his subjects totally at ease and to capture them with these introspective feelings on their faces". It is that sense of captured introspection, perhaps, that sets Bergman's work apart.

He has doggedly pursued his craft since dropping out of college at 20, seemingly convinced of his greatness despite the long years spent in artistic obscurity. In 1966, he saw Robert Frank's seminal book The Americans and later told an interviewer that it taught him "the main thing one needed was a personal vision, and the main thing one needed to serve that vision was intuition and feeling". That is what he has been refining ever since, though his single-minded pursuit of the intuitive and the emotional may have been what kept him out of step with an art-photography world that has consistently preferred the highly formal, the conceptual or – latterly – the deadpan.

Bergman started shooting in colour in 1985. He uses an inkjet printing process to create the soft translucent tones in his photographs, the aura of mysterious light that sometimes seems almost holy. In a recent interview, he suggested: "Putting the colour film in the camera was an act of self-destruction; it was an act of acknowledging defeat because I felt the work would not enter the world, would not enter history because of the institutions that were in force …"

'Anonymous' ... Untitled, 1989. Photograph: Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London/Robert Bergman

'Anonymous' ... Untitled, 1989. Photograph: Courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Hoppen Gallery, London/Robert Bergman

Intriguingly, Bergman refuses to title his photographs or identify his subjects by name, insisting that "I don't want you to have any escape from simply reacting to the art." This has angered one American critic, Andy Grundberg, who, in a review in Aperture magazine this summer, wrote – I think unfairly – that "there's a temptation to dismiss Bergman's pictures as latter-day Bowery bum photography". Directly evoking the spirit of Susan Sontag's book, Regarding the Pain of Others, Grundberg also questioned Bergman's motives. "Surely he can't be concerned that these pictures in any way improve the lives of people they portray, since we don't know where or who they are?"

I find this odd and oddly old-fashioned. You could as easily argue that the anonymity of Bergman's street people is the very point: we pass by people like these every day, maybe just catching their eye for a brief moment then passing on, each of us cocooned in our own thoughts. There is no room, in Bergman's photographs without words, for sentimentality. Nor is his intention to shock or startle or even gently nudge us into a greater awareness of homelessness or the plight of the outsider. There is something else going on here – something deeper, more enigmatic and mysterious.

Bergman, one senses, is, like Robert Frank, an outsider by temperament. He told the Wall Street Journal reporter of an encounter with a man in the Bronx who asked the photographer where he came from. When Bergman told him he came from Minnesota, the man replied, "You come all this way to photograph yourself." Perhaps that penetrating comment gets closest to the mystery at the heart of Bergman's intensely poetic portraits.

No comments:

Post a Comment